Many tax authorities use public shaming as a penalty for tax non-compliance. Yet, we lack empirical evidence on how the introduction of naming and shaming affects behaviour.

Beyond anecdotal evidence, we know surprisingly little about how the introduction of naming and shaming impacts overall compliance. Conceptually, the effect of public shaming on tax revenue is ambiguous. On the one hand, the literature on social pressure (surveyed in Bursztyn and Jensen 2017) highlights that many people care about what others think of them. Increasing the observability of non-compliance may thus prevent taxpayers from engaging in it. On the other hand, shaming can backfire if it informs taxpayers that others are non-compliant (Gino and Ariely 2009, Blaufus et al. 2017) or if it crowds out a taxpayer’s intrinsic motivation (Bénabou and Tirole 2003, Boyer et al. 2016). Whether shaming of tax delinquents increases or reduces tax revenue is ultimately an empirical question.

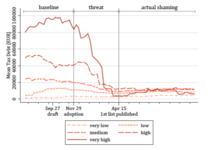

To make progress on this question, we study a new policy that shames taxpayers with outstanding tax debt on the internet (Dwenger and Treber forthcoming). Our analyses show that taxpayers strongly respond to the shaming law. In particular, they pay tax debt in order to avoid shaming. Overall, we find that the shaming law reduces tax debt by about 8.5%. This is remarkable given that the bulk of tax debt was considered uncollectable with standard enforcement instruments. Shaming can thus be a very effective tool for improving tax compliance.